A. THE RIDDLE OF SONNET 136

I. Introduction

II. The identity of the Dark Lady and the poet's relation to her

III. TEXT; The

poet's motives and main constructional ideas

B. Initial and Final Letters of Lines (I)

C. Gematric

Values of Whole Sonnet

D. Latin Reference Models

s.a. Gematric

parallels of Shakespeare's and Ovid's epitaphs

1

extinct external link is marked in grey .

I. Introduction

Recently

(Nov.2008) a friend of mine, an amateur of numerology, asked me for my opinion

about the riddle in Sonnet 136 introduced in lines 7 and 8:

In things of great receipt with ease we prove

Among a number one is reckoned none.

So far I have been concerned only with

gematrical researches of Latin classical literature which I wrote in German. I

don't know anything about Elizabethan concepts of numerology and haven't found anything

reasonable in internet sources. I first supposed the word none might refer to the cipher 0 so that if you take it away from 10 there is still one (1) left.

And in fact, the figure 10 plays a significant

role in the poem. When I inquired about Shakespeare's mysterious Dark Lady in his sonnets, however, I got some enlightening

ideas which might solve the riddle.

II. The identity of the Dark Lady and the

poet's relation to her

1.

Years ago I bought a book

about the Sonnets by A.L.

ROWSE (published 1973), who was confident to have

eventually established the identity of that mysterious woman as EMILIA LANIER (also

AEMILIA LANYER). She was born about 1569 the daughter of an Italian court

musician, Baptista Bassano. At the age of about 17 she became the mistress of Henry

Carey, Lord Hunsdon, Shakespeare's company patron. After becoming pregnant she

was married off to Alfonso (or

Alphonse) LANIER,

another court musician. Cf.more

about EMILIA

Rowse's

researches were not without faults. Thus the first name of his Lanier was William, not Alfonso. This obvious

error led Rowse to assume the Dark Lady's husband to be a rival William – with

consequences for his interpretations of the sonnets.

Two

other favoured claimants to the illustrious title of Dark Lady are Elizabeth Vernon, later

married to Henry Wriothesley, third Earl of Southampton,and Mary Fitton. But

those who patiently follow my line of argumentation required to explain

Shakespeare's intricate art of composition and concealment will once for all

exclude those two respectable ladies from poetic immortality.

2. Shakespeare was under the

Dark Lady's spell although he knew that she had various lovers, perhaps not so

many as Shakespeare's sonnets suggest. He makes no bone about his sexual

fascination. In fact, he indulges in shortening his forename WILLIAM to WILL, thus allowing him to make ample use of equivocal

speech. Beside being a modal verb, will

was understood as

a) sexual desire

b) sexual organ

In sonnet 135, which can be regarded as preparatory for sonnet 136, Shakespeare uses the term will as frequently as 13 times. Unequivocal

sexual speech is contained in lines 5 and 6:

Wilt thou, whose will is large and spacious,

Not once vouchsafe (grant) to hide my will in thine.

In sonnet 136 will occurs

7 times, in greater variation than in 135:

|

name |

l.3 |

Will admitted |

|

|

l.5 |

Will will fulfil |

|

|

l.14 |

my name is Will |

|

modal

verb |

l.5 |

will fulfil |

|

sexual

desire |

l.2 |

I was thy will |

|

sexual

organ |

l.6 |

with wills, my will |

3. Shakespeare had his

reasons for concealing the lady he was so fervently in love with, and the

literary genre of the sonnet may account for some others. At any rate he

ingeniously succeeded in his purpose.

Concealing speech is to be seen as a

literary device. The poet relies on an implicit agreement with the reader, who

accepts cryptic speech as long as it is wittily accomplished. But Shakespeare

is too good a poet as to ignore one deeper sense of poetry, i.e. to elaborate

some truth for himself, not only to address the reader. This implies that the

poet avoids lingering in a mere realm of phantasy. There is an ultimate

rational logic in the art of concealment, very intricate perhaps, but not

beyond comprehending: concealment is wrapped in riddle.

III. The poet's

motives and main constructional ideas

1.

This chapter should be preceded by the text in today's and historic

spelling:

|

1. If thy soul check thee that I come so near, 2. Swear to thy blind soul that I was thy

Will, 3. And will, thy soul knows, is admitted there; 4. Thus far for love, my love-suit, sweet, fulfil. 5. Will, will fulfil the treasure of thy

love, 6. Ay, fill it full with wills, and my will one. 7. In things of great receipt with ease we

prove 8. Among a number one is reckoned none: 9. Then in the number let me pass untold, 10. Though in thy store's account I one must be; 11. For nothing hold me, so it please thee hold 12. That nothing me, a something sweet to thee: 13. Make but my name thy love, and love that still, 14. And then thou lovest me for my name is 'Will.' |

1. If thy ſoule check thee that I come ſo

neere, 2. Sweare to thy blind ſoule that I was thy Will, 3. And will thy ſoule knowes is admitted there, 4. Thus farre for loue, my loue-ſute ſweet fullfill. 5. Will, will fulfill the treaſure of thy loue, 6. I fill it full with wils,and my will one, 7. In things of great receit with eaſe we prooue, 8. Among a number one is reckon'd none. 9. Then in the number let me paſſe

vntold, 10. Though in thy ſtores account I one muſt

be, 11. For nothing hold me,ſo it pleaſe

thee hold, 12. That nothing me,a ſome-thing ſweet to thee. 13. Make but my name thy loue,and loue that ſtill,

14. And then thou loueſt me for my name is

Will. |

2.

No doubt, Shakespeare suffered from his infatuation with the Dark Lady,

but first of all, he was deeply in love and admired her. He certainly reflected

on why he was so much attracted to a woman whom he had to share with other men.

Fate itself must have brought them together. Searching for the inner bond of

their souls and bodies, he found identical letters in her name and his: EMILIA and WILLIAM; the Latin plural form MILIA means THOUSANDS.

3. The Latin letter E means out of. The correct Latin form would be E MILIBUS. But

a poet might neglect this incorrectness.

EMILIA was also spelled AEMILIA. If you count the letter A as 1,

because it's the first letter of the alphabet, the Dark Lady's name could be

understood as ONE OUT OF THOUSANDS.

Shakespeare could interpret this

paraphrase of his lady's name in two ways: First, among thousands of women AEMILIA is the one he fell in love with because

she possessed such exceptional qualities. And second, he could see himself as

one AMONG thousands of lovers. But of course, if

you take the A = 1 away from the name, then the amount of 1 is still

included in the term out of thousands,

and besides, the loving poet is still part of her full name A-EMILIA.

4. If this possibility of

giving meaning to the names AEMILIA

and EMILIA is correct, line 6 with the poet's strikingly generous offer has a

preparatory function for the intended riddle:

Ay,

fill it full with wills, and my will one.

The word group and my

will one means plus

my will.

1.

If we find numerology in one aspect of a poem, we may assume to come

across it in others, too. This for example applies to the number of words in

each line:

|

line |

1 |

2 |

3-5 |

6 |

7-12 |

13 |

14 |

|

words |

10 |

10 |

|

10 |

|

10 |

10 |

|

20 |

25 |

10 |

50 |

20 |

|||

The symmetrical structure of word units reveals

two characteristics: lines with 10

words and ratios of 2:1 or 1:2 respectively.

The first edition of 1609 has the two hyphenated word compounds loue-sute and some-thing, which to regard as two words in the first case and one

word in the second should not arouse any bewilderment.

There are 5 lines with 10 words, and another 50 words in lines 7-12. The first two lines and the concluding couplet

correlate to the single sixth line, and 3:6 lines with 25:50 words both comply with the ratio pattern 1:2.

2. In this way the 14 lines are divided up into 5 word units which match the 5 letters of MILIA.

If one adds the line numbers

symmetrically, the result is 15 for each pair: 1+14, 2+13 etc.

15 is the sum of the numbers 1-5. If line 6 is added for a sixth letter, MILIA becomes EMILIA.

3. The Latin word MILIA was an obvious motive for Shakespeare

to avail himself of the Latin letters denoting numbers, here M = 1000, I = 1, L= 50. He realised the correspondances in his

and the lady's name W-ILLI-AM and

EM-ILI-A. So we can conclude that the poet's

structural 2:1 ratio was inspired by double L in his and

single L in his lady's name.

At this point an example of gematria should be

suitably anticipated. L is the

initial letter of LOVE whose gematric value is 50. Shakespeare employs LOVE 6 times in an elaborate pattern:

|

line |

4 |

5 |

13 |

14 |

36 |

|

LOVE |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

|

There is a parallel ratio of 2:1. Moreover, the sum of the line numbers

is 36 which corresponds to the 4 letters I (I = 9) in W-ILLI-AM and

EM-ILI-A. By the way, the remaining letters also show the 1:2/2:1 pattern: W-AM, EM-A.

4.

Lovers may try to

strengthen their union by intermingling their names. Thus Shakespeare may have

formed the singular form MILLE, giving it a male connotation, and the plural MILIA as its

female counterpart.

5. To sum up, the relevant

parallel elements of the two names consist of 7 letters, 4 I and 3 L, which are at the same time Roman

characters for numbers. Three L total 150,

four I 4, that's together 154, which is the total number of

Shakespeare's sonnets. 154 can be divided by 11,

leaving 14 as the second factor. Thus the Roman

number letter L

for 50 returns as the 11th letter of the alphabet, while 14 is the number of sonnet lines and the letter O in the order of alphabet. The two

factors add up to 25,

which is a main constituent in the arrangement of the 125 words of the sonnet. This brings us back to the

word LO-VE with the same gematric value of 25 for the first and the second part of the word (11+14 – 20+5).

There is still more in

the name LO-VE if the two aspects of

numeric value and number character of the two halves are combined: 25+50 = 75; 25+5 = 30. The two sums add up

to 105

which connects LOVE to the sonnet form of 14 lines, which in

successive addition from 1-14 total 105. The two numbers can

be divided by 15, so their ratio is 5:2. The separation of

LOVE into two halves and the additional count of the number letters accounts

for Shakespeare's ingenious arrangement of words in the 14 lines.

1.

There is no end for lovers to play with names and letters in order to

find unique meanings for their relationships. As to Sonnet 136 gematric practice

may not be strictly proved, but given some probability by plausible findings.

The Elizabethan alphabet consisted of 24 letters:

|

Lett. |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

H |

I/J |

K |

L |

M |

N |

O |

P |

Q |

R |

S |

T |

V/U |

W |

X |

Y |

Z |

|

NV |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

2. Let's look at MILLE (48) and MILIA (42) another

time. The first and last letters have together the number value 30. This coincides with the numbers of the first and last two lines

(1+14+2+13). The remaining number value is 60, which provides another 1:2

ratio.

3. The poet's special

attention might have been attracted by the identical groups of letters in WILLIAM and EMILIA. Their number

values are 40+29 = 69 which is the sum of the line numbers 3-5 and 7-12 (45+24). The remaining value 36 is

equivalent to 4 letters I.

The gematric value of NUMBER is also 69, which is a further motive for the

sonnet's theme of mathematic experiment.

Now riddle line 8 deserves a second

look: Between among a number there are two A with the value 1. The gematric value of AMONG is 47, the same as EMILIA's. There is no

further A in line 8. So perhaps the first A of AEMILIA could be taken away from AMONG, which is not only the initial of the word but of the whole

line, and the second A added to MONG(A) = EMILIA. Alternatively the second A, which

stands alone and is between among and number, might be picked

out. No doubt Shakespeare played here fancifully and wittily.

Line 8 is the only one to consist of 28 letters, which is 4*7 to signify EMILIA's gematric value.

If Shakespeare counted the numbers of

verses, he was naturally aware of their complete sum of 105.

Splitted up into 10+5, it shows the well-known ratio 2:1 again.

Furthermore, 1 and 5 are key

numbers for the letters A and E which we have encountered in the words MILLE and MILIA. Above

all, however, the two numbers represent the first two letters of AEMILIA.

4. Shakespeare plays with

four names: WILL (52) – EMILIA (47)

and WILLIAM

(74) – AEMILIA (48). The

first combination consists of 4+6 = 10

letters. The perfect relationship between a loving couple is seen in the notion

of a mirror image. This can be represented by the Roman numeric letters IV and VI. The two letters denote 1 and 5 and thus

again A and E.

The idea of a mirror is also evident in the

inverse numbers 47 and 74 which add up to 121

= 11*11. The letter L as 11th letter of the alphabet is thus related to the ratio 1:2/2:1. Adding up

the number values of the second name combination (74+48) and appending to it

the sum of the first (52+47), one again gets two inverse numbers: 122 and

221 recalling the 5 lines with

10 words in each.

Of course, WILLIAM and AEMILIA

both consist of 7 letters and so not only fit ideally

together as persons but are also perfectly suited to be dealt with in 14-line

sonnets.

5. There is a last, perhaps

more playful but also significant aspect of inversion: The first and last

letter of the poet's first name is W and M which, as

capital letters, have inverse forms. They could be associated with the initials

of Woman

and

A look at the sonnet shows that W dominates

the first half and M the second:

|

|

W |

M |

total |

|

lines 1-7 |

13 |

4 |

17 |

|

lines 8-14 |

2 |

14 |

16 |

|

total |

15 |

18 |

33 |

The occurrences of W and M of the

entire sonnet amount to 33, the sum

of 12+21, each half divided up into the nearest

halves of 33,

17+16. The counterpart

letters are in one case adjacent (13+14),

in the second proportional (4:2

= 2:1).

What can the distribution of the two

letters mean? The poet is going to devise a new conception of his relationship

to Emilia. This objective may be symbolized as a way from the first letter to

the last. The W may stand for irrational dependence on female

attraction. What the poet strives for is a new Male self-assertion. EMILIA

on the other hand is, by

female nature, oriented towards the Male principle. In this way the poet has

reached the right order of nature at the end of the sonnet.

Sonnet 136 shows that the basis of true

art is form, even mathematical structuring.

6.

If Shakespeare attributed special importance to the 4+3 parallel and inverse letter groups ILLI and

|

1. If thy ſoule check thee that I come ſo neere, 2. Sweare to thy blind ſoule that I was thy Will, 3. And will thy ſoule knowes is admitted there, 4. Thus farre for loue, my loue-ſute ſweet fullfill. 5. Will, will fulfill the treaſure of thy loue, 6. I fill it full with wils,and my will one, 7. In things of great receit with eaſe

we prooue, 8. Among a number one is reckon'd none. 9. Then in the number let

me paſſe vntold,

10. Though in thy ſtores account I

one muſt be, 11. For nothing hold me,ſo it pleaſe thee hold, 12. That nothing me,a ſome-thing

ſweet to thee. 13. Make but my name thy loue,and loue that ſtill, 14. And then thou loueſt me for my name is Will. |

|

|

I |

L |

total |

*11 |

|

value |

9 |

11 |

|

|

|

lines 1-7 |

22 |

29 |

51 |

47 |

|

lines 8-14 |

11 |

12 |

23 |

21 |

|

total |

33 |

41 |

74 |

|

|

*11 |

27 |

41 |

|

68 |

The total number of letters is 74, which is the numeric value of WILLIAM and also FULFILL (l.5).

The frequency of the letter I corresponds to the numeric value of LL and L. In

this way the total result is divisible by 11, the numeric value of L.

The result of lines 1-7 divided by 11 is 47,

corresponding to the numeric value of EMILIA. The anologous result 21 for

lines 8-14 leads to the inverse numbers 12/21 by the addition 12+9 = 21.

51 can be seen as the sum of the two

number letters I+L

= 1+50.

Other numbers may be relevant, too, but

I can't attribute them to any meaning.

1. It has become obvious that

Shakespeare associates the letter L with the initial of Love, the basis being the common letters of W-ILLI-AM and EM-ILI-A. He provides five significant concepts to make us

understand his philosophy of LOVE: L:LL = 1:2, WILL, WILS, FUL(L)FILL and the letter I.

2. L is the 11th letter of the alphabet. The two ciphers

11 signify the IDEA of personal love between two equal partners,

especially between man and woman.

One L assigned to one person means that each individual is gifted

with the capacity of love. It further indicates that love is a matter both of

mind and body, spiritual and sensual.

3. While 1:1 refers to the principle of equality, a different

ratio is required to symbolise the specific relationship between man and woman.

Shakespeare chooses a L:LL = 1:2 ratio. It basically suggests a state of unequality

between the two sexes which tends achieve unity by unification.

The question why one L is assigned to the female sex, double LL to males, is rather speculative and should not be

taken too literally. Perhaps one could say that women are the origin of human

life and that their male offspring continue procreation.

4. The term WILL refers to the sexual organ of both sexes. This

means that sexual union is potential love of equally soul and body. The verb

for this unity is FULFILL written in one word.

Sonnet 136

avoids the word WILL for the female sex, but uses the paraphrases

"treasure of thy love" and "things of great receit".

5. WILS with one L obviously lacks the constituent of spiritual love.

The poet refuses to compare his love with his rivals'. Lack of spiritual love

turns the copulative act into mere gratification of sexual lust. The splitting

up of FULLFILL in FILL FULL shows that

there is no real communication between two partners.

6. The Ls in W-ILLI-AM and EM-ILI-A are framed by the letter I, which shows a close relationship to L: It has the value 1 as a number letter and so two ciphers 1+1 mean the same as number 11, which is the position of L in the alphabet. Furthermore, its position on

number 9 of the alphabet makes it a mirror image

of 11 if you write 9 in Roman numbers: IX–XI.

7.

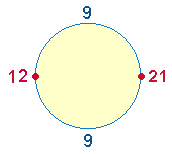

The ratio 1:2 can be

inverted into 2:1 and back again. If both ratios are

written as two-digit numbers, the difference between 12 and 21 is 9 , a space in which the relationship between the

two sexes develops with changing perspectives and impulses . It can be shown as

a movement on the arc of a circle:

|

|

VII. Analysis and

Interpretation of Contents

1. Emilia Lanier implies four

conflicts for Shakespeare:

– He has an extramarital

love affair with her.

– She is unhappily married.

– He is utterly involved in

love.

– He has to cope with

rivals.

Perhaps without knowing, Shakespeare was

trying the impossible: to give and receive love in perfect unity of soul and

body. He might have been encouraged to do so as he imagined Emilia had never

met with true love before. His self-pride was immensely hurt that Emilia gave

her favours also to other men. When he resigned himself to the inevitable, he

at least wanted to assert his true feelings to his lady.

2. In the first line the poet

imagines that his lady keeps up an emotional reserve towards him. Assuming a real

situation, we may imagine various reasons for her restraint. Shakespeare

himself suggests or pretends that she is disquieted by his sexual

impulsiveness. In fact, Emilia may have feared to get more involved in her

relationship to the poet than she really liked and tried to protect her

personal freedom. Shakespeare tries to assure her that she keeps up false

pretenses (blind soul), but if she is sincere to herself, she must confess that

she truly longs for him (thy will).

As a conclusion, in line 4, the poet

entreats her to grant him a new common experience of love fulfilment.

3. In using the word LOVE three times in lines 4 and 5, he

assures her that the love he is going to give her is ruled by sincere feelings,

not just by sexual desire. He further expresses his ardent emotion of love by

addressing her as "sweet" (noun).

The poet promises to "FULFILL the treasure

of thy love". FULFILL in its

original spelling matches single L in EMILIA and double-LL in WILLIAM,

and written as one word signifies their love as a union of

soul and body. Moreover, the numeric value of FULFILL and WILLIAM are both 74, the number of letters is the same, too.

But this prospect of perfect love

reminds the poet that Emilia gives her favours to other men, too. He cannot

imagine that they are able to love his lady as much as he does. Their motives

are incomparable to his. He feels that Emilia betrays their love if she accepts

the advances of other men, too. He denies them true love. He illustrates this

be inverting FULFILL to two separate words FILL and FULL

with altogether 4

L.

The poet's change of mood is not easy to

explain. Is it a kind of self-punishment to share his love with thousands of

other men? Does he accept the facts about Emilia's character? Is he overcome

with disdain towards his lady?

It is at this point that he comes across

the idea of trying a new start for his love by punning on the lady's name A-E-MILIA.

4. In line 7 the poet speaks

of "things of great RECEIT" in a double sense: he thinks of the

numeric dimension of MILIA and

connects it to EMILIA's "treasure of love", room

perhaps for many lovers. RECEIT should also be understood literally, not only

metaphorically, as receiving is the main constituent of female nature. It's by

receiving that a woman can give from the treasure of her love potential. The

word "things" is later resumed by "nothing" (l.11,12) and

"something" (l.12).

It's the poet's intention to make the

notion of sexual desire on his part disappear so that the lady's initial

apprehensions as to sexual advances she might perceive as indecent are

dispersed. He is ready for a new unconditioned round of their love relation.

5. Lines 11 and 12 present

another example of inversion:

For nothIng hoLD Me

hoLD that nothIng Me

The four Latin number letters, which can

be arranged to the word MILD, have

as a result the inverse number 1551. The

letter equivalents of the inverse numbers can again relate to the two name

forms of his lady: AEMILIA and EMILIA. In a jocular way the poet might say: If you reject

me as AEMILIA, accept me again as EMILIA.

Hidden in 1551 is the prime factor 11 which can be equated with the letter L for LOVE.

The Latin word NIHIL for

NOTHING has the number value 50 that is

rendered by L. The number letters IIL mean 52, which is the numeric value of WILL. The three number letters are contained

both in EMILIA and WILLIAM so that a certain awareness of nothingness would

suit both lovers. Besides the word components MILIA (42) and MILI

(41) have the same numeric value as NOTHING

(83). This establishes a common basis between both persons.

From an internet

source I take

the information that NOTHING and SOMETHING "were slang terms

for sexual organs". It makes Shakespeare's intention clear: Sexuality

should not be separated from personality, it is an expression of mutual

acceptance, estimation and affection which stem from the centre of a person's

nature. The poet wants to say: My sexual organ is identical with my personal

self: Regard my organ as being my own self and what I am like as a person, I am

alike when having intercourse with you.

The phrase "a something sweet to you" serves two purposes: It explains

the meaning of preceding nothing, and

it indicates the beginning of sexual activity as a result of vivid imagination.

The word sweet is repeated from line 4. If the poet's

organ is sweet to her, it's the same as if she called himself sweet as, in

fact, he has called her before.

6. The last two lines sum up

what has become clear before already: Love takes its origin from the spiritual

nature of a person. A person's name represents everything he or she is like. So

the poet calls upon his lady to see his person first and take sexual

relationship as an authentic expression of his person. And he furnishes

irrefutable proof of it: His name is Will and so is the name of his male organ.

The phrase

"and love that still" means "go on loving that". The word

"that" resumes the meaning of "that nothing"

from the preceding line, just as "my name" takes up "me".

7. A concluding word should

be. We mustn't forget that Shakespeare addresses his beloved lady in the

sonnet, so he composed it for her.

EMILIA was not just a loose harlot, but

an educated woman, who wrote poetry herself. The poet and she certainly took

pleasure in having lively and witty conversations and also playing fancifully

with their names. There is no reason why Shakespeare should not have sent the

poem to Emilia. And she was intelligent enough to solve the riddle.

The formal devices employed in the poem

might give encouragement for further studies about the Dark Lady, with a chance

to confirm her as Emilia Lanier at last.

After intensively studying the sonnet,

I'm inclined to believe that Shakespeare's original was carefully copied. If

so, we may state the rare case that a poet uses different spellings for the

same word in order to express certain meanings that could be associated with

those differences. In Sonnet 136 there are two occurrences of different

spelling: fullfill – fulfill; will – wils.

There seems great probability, that

Shakespeare was familiar with gematria. Whether he had ideas about the meanings

of numbers in general, I dare not say, though. Too little historic information

is known or available about numerology and gematria at the Elizabethan Age.

People seem to be more interested in mysterious kabalistic knowledge than in

clear mathematical logic.

Written:November 2008